Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts

The project: convert a dormant post office into a destination performing arts center. The site: the historic Crescent Drive Post Office , opened in 1934 and recognized on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Conventional wisdom: place the main theater space into the original mail workroom, adding a wing to hold the plan’s additional elements. Our vision: give a new purpose to the building without implementing any major alterations, transforming the site while preserving the spirit of one of Beverly Hills’ most enduring cultural landmarks.

, opened in 1934 and recognized on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Conventional wisdom: place the main theater space into the original mail workroom, adding a wing to hold the plan’s additional elements. Our vision: give a new purpose to the building without implementing any major alterations, transforming the site while preserving the spirit of one of Beverly Hills’ most enduring cultural landmarks.

Our work on The Wallis consisted of essentially two equally significant projects: the construction of an entirely new annex to house what would become the 500-seat Goldsmith Theater, and the rehabilitation and re-purposing of the original post office building into an auxiliary space, complete with a 150-seat theater, education wing, and various support spaces to the main venue.

Additional Credits: Freeman Group (Owner's Representative), Rothamn Engineering (Civil Engineer), Structural Focus (Structural Engineer), ARC Engineering (MEP Engineer), Schuler Shook Theatre Planners (Theatre Consultant), HLB Lighting (Lighting), Lutsko Associates (Landscape Architect), Jaffe Holden (Acoustic Engineer), Electrosonic (AV Consultant), HKA Elevator Consulting), Independent Roofing Consultants (Waterproofing), MATT Construction Group (Pre-construction/Estimator), Historic Resources Group (Historical Consultant), Roland Halbe (Photography), Steve Proehl (Aerial Photography)

The History

The story of modern-day Beverly Hills begins in the first months of the 20th century, when a group of oilmen descended upon the area, buying the land from local ranchers in 1900. Failing to find any oil, they instead discovered enough water to justify developing a town and began building homes and selling plots in 1906. Beverly Hills was incorporated in 1914, and by the mid-20s civic infrastructure began to solidify the community.

The need for a post office obvious, initial planning for the project was plagued by financial difficulties exacerbated by a funding impasse with Congress. Vaudevillian, humorist and honorary mayor of Beverly Hills Will Rogers spearheaded the city’s campaign, writing a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon in 1930: "It seems you owe us $250,000 to build a post office and they can’t get the dough out of you, and I told them I knew you and that you weren’t that kind of fellow at heart. So in place of suing you, why, he is going back there and see if he can’t jar you loose from it."

spearheaded the city’s campaign, writing a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon in 1930: "It seems you owe us $250,000 to build a post office and they can’t get the dough out of you, and I told them I knew you and that you weren’t that kind of fellow at heart. So in place of suing you, why, he is going back there and see if he can’t jar you loose from it."

Rogers’ letter generated a prompt visit and site tour from D.C. officials, resulting in $300,000 of federal funds earmarked for what became the Crescent Drive Post Office. Led by architect Ralph C. Flewelling alongside consulting architects Allison & Allison, the original building was designed in the Italian Renaissance Revival style and consisted of a double height grand lobby clad in marble with a barrel-vaulted ceiling flanked by single-story transition spaces on both sides. Initial work began in 1931, and the Los Angeles firm Sarver & Zoss broke ground on the project in early spring 1933. The cornerstone was laid on Wednesday, November 15th, 1933, and the facility officially opened on April 28th, 1934.

Along with (and just down the block from) City Hall (completed in 1932) , this building stands as one of three major civic institutions built during the Depression, forming the backbone of what would become modern-day Beverly Hills.

, this building stands as one of three major civic institutions built during the Depression, forming the backbone of what would become modern-day Beverly Hills.

An Uncertain Future

Despite successfully serving the community for over six decades, the city’s postal operations eventually expanded beyond the capacities of their Crescent Drive Home, moving to a larger facility a few blocks away on North Maple Street in 1990. Officially included on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, the Postal Service deemed the building “surplus property” in 1993. The property’s future temporarily uncertain, the City of Beverly Hills purchased the historic post office in 1999 with the intention of turning it into a cultural venue, honoring and extending the space’s civic origins.

Although the City’s board shared a common vision for the site, the project went through years of pre-development; much like the circumstances surrounding the construction of the original post office, funding was an early and constant challenge. Lou Moore, former executive director of The Wallis and responsible for overseeing the theater’s decade-plus fundraising, design, and construction cycle, ultimately raised tens of millions of dollars. Theater namesake and super-philanthropist Wallis Annenberg provided two significant contributions, initially making a $15 million gift to the organization, followed by a second of $10 million.

provided two significant contributions, initially making a $15 million gift to the organization, followed by a second of $10 million.

All told, the total cost that went into creating the center is estimated to be $75 million.

We Need a Story

Our involvement with the project began in 2006 when the city issued a third RFP inviting architectural firms to re-think the site. Previous design iterations had focused on the idea of transforming the existing post office structure into the central performing venue, opting to build an adjacent annex to house the various supporting and educational components. Our proposal pitched the opposite, instead assimilating the auxiliary requirements and education wing into the post office and constructing an entirely new structure to serve as the main theater space. The advantages of this plan were two-fold: it allowed for more concentrated and detailed rehabilitation and restoration efforts of the historic post office’s original architecture (which would have been largely lost in such a drastic programmatic upheaval), while also creating the possibility to design a modern performing arts facility from the ground up, unconstrained by the original building’s inherent outlines and limitations.

Despite the sound rationale of this layout, it represented such a drastic reversal in strategy that the board was initially hesitant—understandable, because after all the already-ambitious rehabilitate and re-use project was now being pitched as an even more complex site redesign, complete with an entirely original monumental and modern theater bringing its own challenges and style.

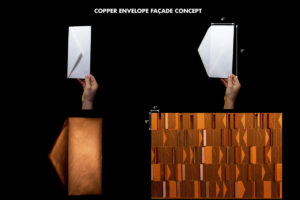

“The reality of it is that I needed a story in order to sell a contemporary building,” says Zoltan Pali, SPF:a founder and Wallis design principal. “I knew I needed a story and the story that came to me was to reference what happened on the site for many, many years: the receiving and dissemination of mail. What if all the mail that passed through here actually came back? The letters, of course, stay with their owners, but the envelopes tossed away for decades actually flocked together and came back and clad the building.”

He was right: we did need a story, and it was this narrative that cinched the project.

Twin T's

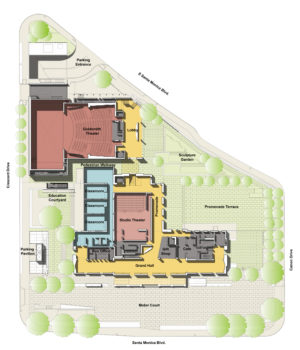

When viewed from above , the building site we had to work with is an irregular quadrilateral bracketed by four streets: North Crescent Drive, North and South Santa Monica Boulevard, and North Canon Drive. The existing post office, T-shaped in design with three shorter wings on both sides and the rear extending from the main building, spans the majority of the lot’s northwestern side, facing out towards North Santa Monica Boulevard.

, the building site we had to work with is an irregular quadrilateral bracketed by four streets: North Crescent Drive, North and South Santa Monica Boulevard, and North Canon Drive. The existing post office, T-shaped in design with three shorter wings on both sides and the rear extending from the main building, spans the majority of the lot’s northwestern side, facing out towards North Santa Monica Boulevard.

Since our plan involved leaving the post office as-is, the most logical place for the new theater was in the southeastern corner, in the triangular area created by the asymmetrical intersection of North Crescent and South Santa Monica Boulevard and previously occupied by parking. As if by kismet, when evaluating the master plans it made the most sense to base the outline of the theater on a similar T-shaped model, an initial major decision that helped establish what became the project’s dominant theme, structurally, aesthetically, and culturally: the strange and often asymmetrical symbiosis between the old and the new.

In nestling these two similar structures Tetris-style in such close quarters we were able to create a near-constant dance between positive and negative spaces, with the interplay between the two buildings establishing a variety of outdoor spaces and structures. Despite having to lower the new theater by sinking deep into the site in order to subordinate the post office’s height, we maintained a logical and uninterrupted route through the center, seamlessly connecting North Crescent (and City Hall) to the dense shopping area beyond South Santa Monica . Although the two buildings never touch, they are connected by a pedestrian walkway and tunnel, and in one of our favorite spaces of the entire project the path narrows to a point where you (very briefly) feel engulfed by the enormity of the two structures

. Although the two buildings never touch, they are connected by a pedestrian walkway and tunnel, and in one of our favorite spaces of the entire project the path narrows to a point where you (very briefly) feel engulfed by the enormity of the two structures (also at this point are two symmetrical windows, one on each building, that provides a clear visual path between the structures through to the streets beyond

(also at this point are two symmetrical windows, one on each building, that provides a clear visual path between the structures through to the streets beyond ).

).

The Goldsmith Theater

Rather than defer to the existing and surrounding architecture, our mission became to create a theater and campus inspired by the daily minutiae of the site: the processing, sorting, and delivery of mail.

The skin of the new theater is our most visible homage to this history, abstracted to represent millions of envelopes that once defined the site: 4’x 9’ envelope-shaped copper-colored concrete panels1 are repeated across the façade. Each “envelope” is slightly different (some flat, some closed, some turned out to the front) and irregularly patterned , giving the building a thoroughly modern aesthetic, distinct, but importantly not aloof from the post office: not only does the abstraction refer back to the old building historically, the copper of the concrete panels reflects the terra cotta color as well.

, giving the building a thoroughly modern aesthetic, distinct, but importantly not aloof from the post office: not only does the abstraction refer back to the old building historically, the copper of the concrete panels reflects the terra cotta color as well.

We viewed this skin functionally as “the final curtain” of the Goldsmith Theater (named after the Wallis’ Founding Chairman, the late banker and philanthropist Bram Goldsmith), as it conceals much of the building’s mechanical equipment on giant shelves hidden in the folds of the exterior cladding. In wrapping the skin so thoroughly it gives singular form to a structure that otherwise would be perceived as separate elements.

The 500-seat theater (350 on the ground floor, 150 in the balcony) is lined with acoustically and visually transparent wood paneling buffered further from the sounds of the street by dense concrete walls. A lobby juts from the theater’s rear, overlooking a courtyard and sculpture garden2 and connected to the post office through a walkway and below-grade staircase.

A Post Office Restored

Inside the post office we executed extensive preservation and restoration work, including but certainly not limited to: a re-roofing effort consisting of salvaging and reinstalling existing Roman-style glazed terracotta tiles, the mending and reactivation of a hidden gutter system behind the eaves, artisan-level refurnishing of slip-glazed bricks and selective repointing of mortar, and re-finishing historic ironwork. In the former atrium-now-Wallis grand lobby, we diligently restored eight historic murals by noted PWA-era artist Charles Kassler3.

Designed to complement the new Goldsmith Theater, we repurposed the building to hold various support spaces, including administrative offices, an education wing, and various back of house areas such as dressing rooms and costume shops. The original mail sorting room has been converted into the 150-seat auxiliary Lovelace Studio Theater , designed as a flexible stage suited for new and smaller work, black box, cabaret, workshops, student performances, and rehearsals.

, designed as a flexible stage suited for new and smaller work, black box, cabaret, workshops, student performances, and rehearsals.

'A Dream in an Envelope'

The Wallis Annenberg Performing Arts Center officially opened on October 17th, 2013, the occasion marked by a lavish opening-night gala under the theme “A Dream in an Envelope” . The glamorous affair included a number of dance and musical performances, live readings of vintage letters that had passed through the post office decades past (written by Tennessee Williams, Groucho Marx, and Tchaikovsky, recited by Diane Lane and John Lithgow, among others), a dinner catered by Wolfgang Puck (filet mignon over white truffle risotto), and a live fashion show by the evening’s sponsor, the Italian design brand Salvatore Ferragamo.

. The glamorous affair included a number of dance and musical performances, live readings of vintage letters that had passed through the post office decades past (written by Tennessee Williams, Groucho Marx, and Tchaikovsky, recited by Diane Lane and John Lithgow, among others), a dinner catered by Wolfgang Puck (filet mignon over white truffle risotto), and a live fashion show by the evening’s sponsor, the Italian design brand Salvatore Ferragamo.

Despite the large number of celebs in attendance—including Sidney Poitier, Jodie Foster, Charlize Theron and Gwen Stefani—the LA Times wrote the next day that the “real star of the evening was the U.S. Postal system itself, not to mention the range of theatrical experiences one can expect to see in the coming years across the two stages of the $70-million, 2.5 acre performing arts campus.”

and Gwen Stefani—the LA Times wrote the next day that the “real star of the evening was the U.S. Postal system itself, not to mention the range of theatrical experiences one can expect to see in the coming years across the two stages of the $70-million, 2.5 acre performing arts campus.”

Productions since the inaugural 2013/14 season have included Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along and Into the Woods and Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night; perhaps most notably, the Wallis was the Los Angeles home of Deaf West Theater’s Tony-Award nominated production of Spring Awakening, which opened in May 2015 before moving to Broadway later that fall.

Notes

-

1

Made out of Swisspearl cement boards, we redesigned the façade to alter the size and modulation of the “gaps” between panels, resulting in 30% savings in material. Swisspearl is made composed of natural raw materials from Switzerland and are “manufactured with low energy consumption and a high level of environmental awareness.”

-

2

An early headline of the garden was the colorful 30-foot sculpture by Roy Lichtenstein Coups de Pinceau, 1988. Temporarily installed in November 2013, the sculpture was relocated to the Lichtenstein foundation in New York City in July 2017.

-

3

The murals on the walls above the marble were commissioned by the Treasury Department under two different contracts. Painted as frescoes, there were actually 8 lunettes, one on each end of the room, “Post Rider” and “Air Mail”, and three on each the north and south sides of the room which as a complete painting were entitled “Construction – PWA”. The murals on the north and south were part of the Treasury Relief Art Project which as created to employ artists during the Depression. The Kassler mural is the only PWA effort in the state of California that shows depression-era unemployment problems. The subject matter was not chosen to criticize the government, but rather to underscore the virtues of the New Deal and to show “the administration’s effort to solve the unemployment problem.”

Awards

- AIA California Council Design Merit Award 2018

- BUILD News Architecture Awards, Best International Museum Architects 2016

- BUILD Architecture Award - Best Beverly Hills Cultural & Performing Arts Project 2016

- AIA|LA Design Awards, Adaptive Reuse/Historic Preservation Citation 2016

- Westside Urban Forum Award, Cultural 2015

- LA Conservancy Preservation Award 2015

- Architizer A+ Popular Choice Award 2015

- NCSEA Excellence in Structural Engineering 2015

- Engineering News-Record Southern California Building of the Year 2015

- Los Angeles Architectural Civic Award 2014

- American Architecture Award 2014

- California Preservation Foundation Design Award 2014

- Engineering News-Record Building of the Year 2014

- Engineering News-Record California Cultural Project of the Year 2014

- Southern California Development Forum, Built Award 2014

- AIA Next LA Award 2007

- Los Angeles Business Council, Unbuilt Civic Architecture Award 2007

Publications

- 10 spectacular performance spaces for your Friday inspiration - Archinect 2020

- New Architecture Los Angeles - Prestel Publishing 2019

- Not All of L.A.’s Architectural Marvels Are Vintage - LA Magazine 2019

- Expressed Delivery - Commercial Design Trends 2016

- See Cool Los Angeles Sites in a Rare View From Above - Curbed LA 2016

- Project Deconstruction - Architectural Products 2015

- Umetnost U pošti - Kuća Stil 2015

- Núcleo Cultural - VD 2015

- Letters to the Sun - Swisspearl Architecture #21 2015

- SPF:a’s Wallis Annenberg Center recognized at California Preservation Design Awards - Archinect 2014

- Setting the Stage - WHERE Guestbook Los Angeles 2014

- SPF:a's Modern Addition - Architect Magazine 2014

- Wallis Annenberg Center: New Beverly Hills Theater Nods to its Past Life as a Post Office - LA Weekly 2013

- Review: Wallis Annenberg Center is a Step Forward for Beverly Hills - LA Times 2013

- Curtain Up - Performances Magazine 2013

- Touring Bev Hills's New The Wallis Performing Arts Center - Curbed LA 2013

- The Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts’ Postal Past - LA Magazine 2013

- Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Set for Grand Opening - LA Times 2013

- Los Angeles to Welcome Wave of New Cultural Buildings - Architectural Record 2013

- Bev Hills's New/Historic Annenberg Arts Center Opens in Fall - Curbed LA 2013